Subsea Cables, Sensing Europe’s Digital Lifelines

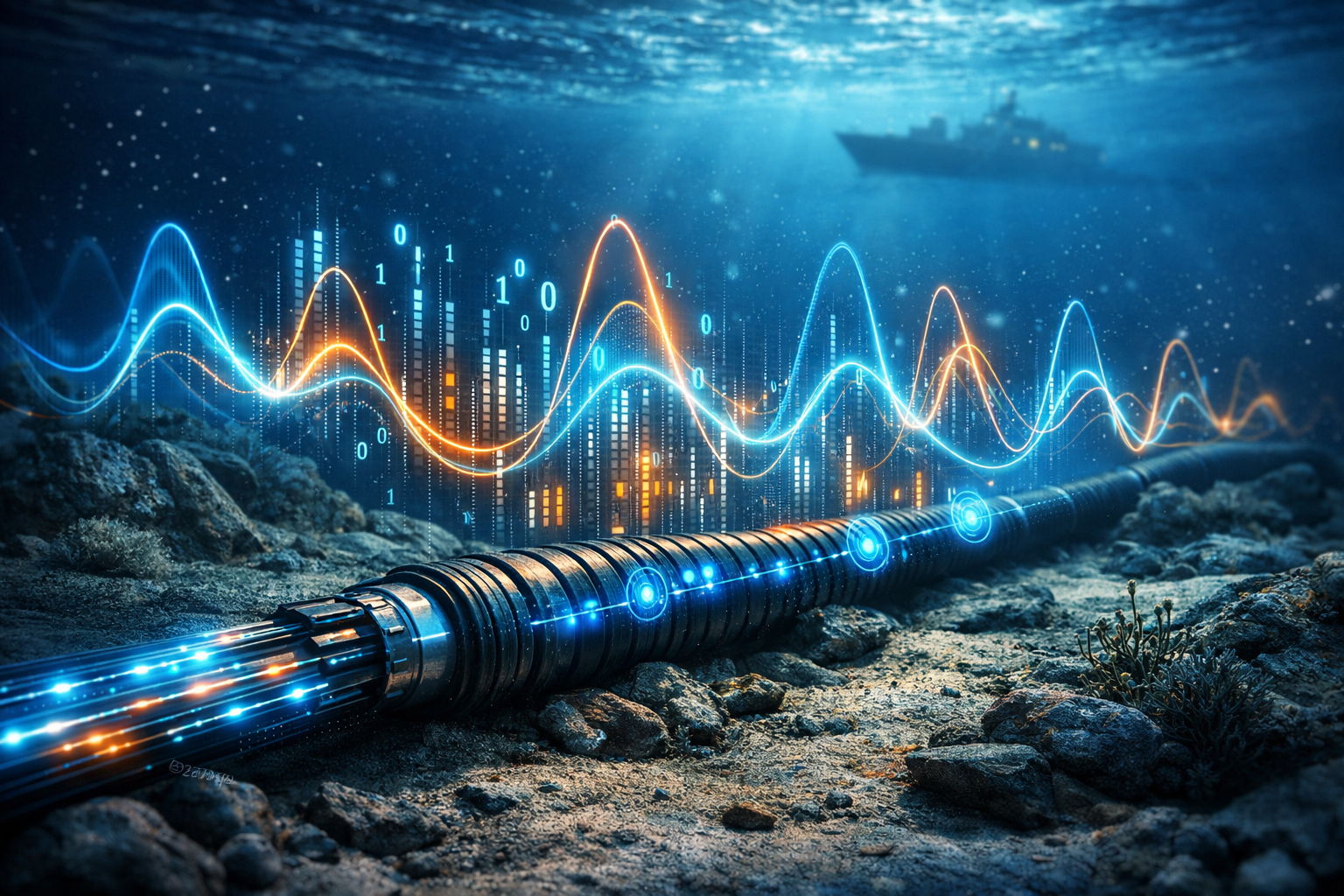

Europe’s digital diplomacy increasingly runs beneath the sea. By turning subsea fibre-optic cables into sensors, new technologies offer a cooperative, non-intrusive way to monitor and protect critical digital infrastructure.

Subsea telecommunications cables form the physical backbone of the global internet. Between 95% and 99% of intercontinental telecommunications traffic is carried by these fibre-optic systems, which together represent approximately 1.4 to 1.5 million kilometres of cable in service worldwide. Cloud computing, artificial intelligence, financial markets, scientific collaboration and public digital services all depend on this infrastructure, most of which lies out of sight on the seabed.

For a long time, subsea cables were treated as essentially passive assets. Once laid, their protection relied on careful routing, redundancy and the availability of repair vessels when faults occurred. Yet the scale, depth and geographical dispersion of contemporary cable systems make continuous physical monitoring impossible through traditional maritime means. As networks have expanded and traffic volumes increased, this limitation has become increasingly visible. The focus has therefore shifted from protection alone to surveillance: the capacity to detect, characterise and localise events that may affect a cable, ideally before physical damage occurs. This shift is underpinned by a profound technological change: the cable itself can now function as a sensor.

Seeing the unseen: why visibility matters

Recent international analyses have highlighted the consequences of limited visibility along cable routes. The article published by the Institut National des Affaires Stratégiques (INAS), “Subsea cables: the invisible infrastructure at the heart of geopolitical rivalries”, stresses how poor situational awareness complicates attribution, early detection and response, particularly in environments where accidental damage, hybrid actions and strategic signalling may overlap.

👉 https://inas-france.fr/cables-sous-marins-linfrastructure-invisible-au-coeur-des-rivalites-geopolitiques/

Cable faults may originate from fishing activity, anchoring, geological processes or deliberate interference, but distinguishing between these causes is often slow and uncertain. What is missing is not only repair capacity, but persistent, fine-grained awareness along the cable route itself. This observation has driven growing interest in continuous, non-intrusive monitoring technologies capable of operating at scale without relying on constant physical presence at sea.

Turning the cable into a sensor

At the core of this evolution lies fibre-optic sensing. Techniques such as Distributed Acoustic Sensing (DAS) and Brillouin-based methods (BOTDR/BOTDA) allow a standard telecommunications fibre to act as a continuous linear sensor over tens or even hundreds of kilometres. Applied to subsea cables, these techniques make it possible to detect vibrations caused by anchors or trawling gear, identify acoustic signatures associated with nearby vessels, localise mechanical stress or deformation along the cable, and observe seismic or environmental phenomena that may precede damage.

Rather than deploying additional seabed sensors, this approach reuses existing infrastructure, transforming a passive transmission asset into an active monitoring system embedded in the marine environment. The main challenge is no longer sensing but interpretation. A subsea fibre continuously records vast quantities of acoustic and mechanical signals, the majority of which are benign. Artificial intelligence is therefore essential to filter background ocean noise, classify events as natural, accidental or anthropogenic, detect anomalies relative to baseline patterns, and support near-real-time alerts for cable operators.

France: observation-driven cable monitoring

In France, work on subsea cable surveillance builds on long-standing expertise in marine sciences and geophysics, with a clear emphasis on observation and measurement rather than coercive protection. Ifremer plays a central role through the FiberSCOPE project, supported under France 2030, which explores how existing subsea cables can be used to monitor physical activity along the seabed using fibre-optic sensing, with direct relevance for cable integrity and early warning.

Complementing this applied work, research conducted by the CNRS, including in laboratories such as Géoazur, has demonstrated that subsea fibres can function as distributed seismic and acoustic observatories, capable of detecting very weak signals over long distances. At the interface between research and operational deployment, Géo‑Océan, based in Brest, contributes to translating these techniques into applied monitoring solutions, combining geosciences, acoustics and data analysis to support continuous cable awareness and anomaly detection.

Ireland’s particular position in the subsea cable landscape

The Irish case unfolds in a different but closely related context, shaped by geography and network structure. Ireland occupies a distinctive place in the global subsea cable system: its west-facing Atlantic coastline makes it one of Europe’s primary landing zones for transatlantic fibre-optic systems before traffic is routed onward to the UK and mainland Europe.

As of 2025, the global submarine cable map lists nearly 600 cable systems and more than 1,700 landing points worldwide. Sector data indicates that around 18 active subsea cable systems land on the island of Ireland, approximately 13 of them in the Republic, creating a relatively high concentration of critical infrastructure along limited coastal areas. Recent filings and announcements of new Ireland–UK and Ireland–Europe cable projects underline sustained demand for capacity and route diversity in this corridor.

This positioning means that events affecting cables in or near Irish waters can have immediate consequences for European transatlantic connectivity well beyond national borders. At the same time, Ireland’s long-standing policy of military neutrality and limited naval footprint naturally favour approaches centred on anticipation, monitoring and cooperation rather than deterrence. In this context, surveillance technologies embedded directly in the cable itself are particularly well suited: they enhance awareness and early warning without altering the broader strategic posture.

Cable-centric surveillance in Ireland

Ireland’s research ecosystem reflects this configuration. Rather than broad seabed observation, work tends to focus on monitoring activity in the immediate vicinity of cable routes. At Trinity College Dublin, the Sea-Scan project explores the use of Distributed Acoustic Sensing on subsea telecommunications fibres to detect vessel movements near cables, identify abnormal or non-cooperative behaviour, and distinguish benign maritime activity from events that may threaten cable integrity.

Artificial intelligence is integrated early in the process to automate signal classification and reduce false positives, an essential requirement for operational monitoring. This work is reinforced by the ADAPT Centre, which develops machine-learning models adapted to large-scale acoustic data streams. Ireland also benefits from SmartBay Ireland in Galway Bay, which provides a real-world marine test environment where fibre-connected systems, environmental sensors and data platforms can be combined to validate cable-monitoring approaches under operational conditions.

From research to deployment

While the primary objective of these technologies remains monitoring and protecting the cable itself, fibre-optic sensing inevitably generates secondary information on maritime activity or environmental conditions. These extensions should be understood as by-products of cable-centric surveillance rather than ends in themselves. The core innovation lies in transforming the cable into a continuous sensing asset embedded in the marine environment.

The Horizon Europe 2026 work programme provides a concrete framework to move these approaches closer to deployment. Within Cluster 3 – Civil Security for Society, several 2026 topics address monitoring and stress-testing of critical infrastructure, anomaly detection and resilience to natural and human-induced events. Cybersecurity actions implemented via the European Cybersecurity Competence Centre (ECCC) further reinforce this approach by supporting large-scale monitoring, situational awareness and the integration of physical sensing data into cyber-security operations.

Conclusion

Subsea cables are no longer merely transmission assets. They are becoming monitored infrastructures, and increasingly surveillance platforms in their own right. By turning the cable into a sensor, Europe is developing a pragmatic, non-intrusive approach to cable security that prioritises early detection, physical understanding and situational awareness over reaction alone.

Research in France and Ireland shows how this model can be implemented in practice, combining fibre-optic sensing, artificial intelligence and real-world experimentation. Horizon Europe 2026 now offers a timely opportunity to move from experimentation to scalable, operational cable-monitoring systems.

These issues will also be discussed at the 2026 Valentia Island Symposium on Subsea Cable Security and Resilience, taking place on 22–24 April 2026 at the historic Transatlantic Cable Station in County Kerry, Ireland.

Official website: https://symposium.valentiacable.com/

Key references

- Institut National des Affaires Stratégiques (INAS) – Subsea cables: the invisible infrastructure at the heart of geopolitical rivalries

https://inas-france.fr/cables-sous-marins-linfrastructure-invisible-au-coeur-des-rivalites-geopolitiques/ - 2026 Valentia Island Symposium on Subsea Cable Security and Resilience

https://symposium.valentiacable.com/