France’s National Strategy on Data and Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare (2025–2028)

France’s new health data and AI strategy (2025–2028) aims to transform care through large-scale datasets, ethical frameworks, and AI innovation, paving the way for more efficient and trusted healthcare

Introduction: Data and Artificial Intelligence at the Core of Health Transformation

Healthcare systems around the world are facing unprecedented challenges. Ageing populations, the rise of chronic diseases, shortages in medical staff, and increasing costs are putting pressure on public health services everywhere. At the same time, digital technologies are offering new opportunities: vast amounts of health data are being generated, and artificial intelligence (AI) is demonstrating its ability to analyze this data at scale, supporting diagnosis, treatment, prevention, and system management.

France is among the countries that have decided not to let this transformation unfold passively but to actively shape it. The French government has put forward a comprehensive national strategy for data and artificial intelligence in healthcare for the period 2025–2028. This strategy is both pragmatic and ambitious: it seeks to build robust infrastructures, foster innovation, and preserve citizen trust, while ensuring that Europe retains sovereignty over the digital future of its healthcare systems.

1. The Global Context: Healthcare at a Crossroads

Around the world, healthcare expenditures are rising faster than GDP growth. In OECD countries, health spending has reached an average of 10% of GDP, and in some nations such as the United States, it exceeds 17% of GDP. France itself spends 12.4% of GDP on healthcare, one of the highest levels in Europe. While this investment demonstrates the importance placed on health, it also raises questions of sustainability.

At the same time, technological innovation is accelerating. The global digital health market is projected to exceed $900 billion by 2030, with AI in healthcare representing $188 billion of that market. AI systems are already capable of detecting diseases such as cancer from imaging data with accuracy rates comparable to, or in some cases better than, experienced clinicians. Natural language processing tools are assisting with medical transcription, while predictive models are being used to anticipate epidemics or manage hospital logistics.

Yet the benefits of these technologies are not evenly distributed. In the United States, private companies have taken the lead, often driven by market incentives. In China, state-led programmes seek to harness massive datasets to fuel AI development. Europe, and France in particular, has chosen a different path: one that emphasizes ethics, regulation, and sovereignty. The goal is not only to innovate but to ensure that innovation aligns with European values, protects individual rights, and serves collective well-being.

2. Why Data and AI Must Be Addressed Together

A central insight of the French strategy is that data and AI cannot be separated. AI systems rely on high-quality data: the more representative, standardized, and comprehensive the data, the more effective and trustworthy the AI. Conversely, data without advanced analytics remains underexploited.

This interdependence has several implications:

- Data as fuel: AI models require massive datasets for training. For instance, an AI for early cancer detection may need tens of thousands of annotated images to reach reliable accuracy.

- AI as a tool for valorisation: Without AI, the potential of datasets such as national insurance claims or hospital records cannot be fully realized.

- Joint governance: Ethical questions—such as transparency, fairness, or consent—apply equally to how data is collected and how AI is deployed.

By adopting a joint strategy for health data and AI, France acknowledges that these two pillars must advance hand in hand.

3. The French Vision: Sovereignty, Trust, and Innovation

France’s national strategy rests on three pillars:

- Sovereignty: Health data is a strategic asset. It should not be left in the hands of non-European companies or infrastructures where legal protections are weaker. Sovereignty ensures that data remains under European jurisdiction and that Europe can set its own rules for AI deployment.

- Trust: Citizens must be confident that their data will be used responsibly. This requires transparency, robust governance, ethical safeguards, and the ability to exercise rights such as opting out. Without trust, even the most sophisticated data infrastructures will face resistance.

- Innovation: Sovereignty and trust are not opposed to innovation; they are conditions for sustainable innovation. By building infrastructures, funding startups, and supporting public-private partnerships, France seeks to create an environment where AI solutions can be developed, tested, and deployed responsibly.

4. A European Responsibility

The French strategy is not purely national. It is embedded in the wider European framework, particularly the European Health Data Space (EHDS) and the AI Act. France has played an active role in shaping these regulations, and its national measures are designed to anticipate and facilitate their implementation.

This European dimension is crucial for several reasons:

- Scale: Many health challenges, such as rare diseases or pandemics, require datasets far larger than any single country can provide.

- Interoperability: Patients move across borders, and research collaborations are international. Data infrastructures must be compatible.

- Sovereignty: Europe must avoid dependency on external players, whether for cloud hosting or for AI algorithms.

France therefore positions itself not only as a national actor but as a European leader in building a sovereign and ethical health data and AI ecosystem.

5. Relevance for Ireland and International Partners

For Ireland and other European countries, France’s strategy offers a concrete example of how to mobilize national resources to build a robust health data ecosystem. Ireland faces similar challenges: managing growing health expenditures, digitalizing health services, and participating in European frameworks such as the EHDS.

France’s experience provides insights into:

- How to structure a national health data system covering the entire population.

- How to balance citizen rights with research needs.

- How to integrate AI into healthcare in a way that supports professionals rather than replacing them.

- How to secure sovereignty while participating in European and international collaborations.

This introduction sets the stage for a deeper exploration of France’s strategy. The following sections will examine how the country has built one of the world’s largest health data infrastructures, how it is developing an AI strategy tailored to healthcare, how concrete use cases are already transforming practice, and how international cooperation, particularly with Ireland, can amplify these efforts.

Part I – Building a National Health Data Infrastructure

1. A Historical Perspective: From Fragmented Records to a National Asset

Until the early 2000s, health data in France, as in many other countries, was scattered across a patchwork of systems. Hospitals kept their own records, insurance agencies stored claims separately, and public health authorities maintained registries that rarely communicated with one another. Researchers who wished to conduct longitudinal studies faced immense difficulties: accessing hospital discharge data could take months, linking it with insurance claims required cumbersome authorizations, and combining it with mortality data was often impossible in practice.

France gradually came to realize that health data, long regarded as a bureaucratic by-product, was in fact a strategic national resource. The 2004 Public Health Act introduced the first provisions for large-scale data integration. By 2016, the country had laid the legal foundations for a unified health data system, culminating in the creation of the Système National des Données de Santé (SNDS) in 2017. This marked a turning point: from fragmented archives to a coherent, longitudinal, and population-wide database.

2. The National Health Data System (SNDS): A Global Benchmark

Today, the SNDS is recognized as one of the most comprehensive health data systems in the world. It covers the entire French population of 67 million people, making it not just a statistical sample but a full-scale mirror of the nation’s healthcare activities.

The richness of the SNDS lies in its diversity of sources:

- Insurance claims/data flows. In 2023, France’s SESAM-Vitale network transmitted about 1.331 billion electronic treatment forms (FSE) from community-based professionals, plus 78.1 million electronic reimbursement requests (DRE). Alongside hospital activity (~19.5 million MCO stays in 2023), these administrative and clinical flows feed the SNDS, which covers ~99% of residents.

- Causes of death (CepiDC): France maintains a comprehensive mortality registry, essential for public health monitoring.

- Long-term care and dependency: Data from elderly care institutions and disability services ensure that the system captures not only acute care but also medical-social dimensions.

- New enrichments: In recent years, vaccination records—including those from the COVID-19 campaign—laboratory results, and imaging datasets have been added or are being piloted.

The SNDS is unique not only in scale but also in its longitudinal dimension, enabling long-term reconstruction of patient care pathways across all healthcare settings. This longitudinal perspective is particularly valuable for chronic disease research (e.g. diabetes), as it makes it possible to analyse treatment history, hospitalisations, complications and outcomes over extended periods

Few countries possess such a system. Denmark and Finland are often cited as leaders in health registries, but their populations are much smaller (under 6 million). The United States has vast data, but fragmented across private insurers, hospitals, and state systems, without a single nationwide database. In this sense, the SNDS places France in a distinctive position: a large country with a unified, population-wide health data system.

3. The Health Data Hub: From Data to Usability

Having data is one thing; making it usable is another. The French government recognized that researchers and innovators often struggled with the complexity of the SNDS: heterogeneous coding systems, lengthy authorization procedures, and limited computing environments. To address this, the Health Data Hub (Plateforme des Données de Santé – PDS) was launched in 2019.

The Health Data Hub plays a dual role:

- Technical platform: It provides secure, cloud-based environments where authorized users can analyze health data without extracting it. The platform includes tools for data management, statistical analysis, and machine learning, reducing the technical barriers to entry.

- Institutional gateway: It serves as a one-stop shop for researchers, hospitals, startups, and companies seeking access to health data. Instead of navigating multiple agencies, applicants can submit a unified request, which is then processed under a standardized procedure.

The impact has been tangible. Since its creation, the Health Data Hub has supported more than 200 projects, ranging from academic studies to AI development. For instance:

- Epidemiologists have used SNDS data to measure the effectiveness of flu vaccination campaigns across millions of patients.

- Startups have trained AI models to predict hospital readmissions, enabling targeted interventions.

- Hospitals have benchmarked their performance against national averages, identifying areas for improvement.

By curating and harmonizing data, the Health Data Hub transforms raw datasets into usable, high-value resources. It also symbolizes the French philosophy: data is a collective good, to be governed in the public interest and mobilized for innovation.

4. Strategic Investments: France 2030 and Beyond

No infrastructure of this scale can function without sustained investment. Under the France 2030 national plan, digital health was identified as a priority, with €650 million allocated to the acceleration strategy, of which €110 million specifically targeted health data infrastructures.

Several flagship initiatives have been funded:

- Hospital Data Warehouses: Sixteen regional consortia, involving 31 university hospitals and numerous general hospitals, have developed interoperable warehouses of clinical data. Their integration with the Health Data Hub allows national-scale research while respecting local autonomy.

- France Cohortes: This initiative supports over 60 active longitudinal cohorts, covering cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, metabolic disorders, and rare diseases. Cohorts are essential for precision medicine, and their integration into the national system amplifies their value.

- FReSH Portal (France Recherche en Santé Humaine): A public portal cataloguing ongoing and completed studies, ensuring transparency and discoverability.

- Primary Care Data Projects: The P4DP programme, involving more than 2,000 general practitioners, is pioneering the systematic reuse of primary care data, long considered a blind spot in the system.

These investments are not just about building databases. They are about creating a national fabric of interoperable, federated data assets, where hospitals, researchers, and innovators can collaborate while maintaining control over their contributions.

5. European Anchoring: The EHDS

France’s strategy is deeply aligned with the European Health Data Space (EHDS), adopted in 2025. The EHDS represents a paradigm shift: it requires member states to make health datasets re-usable by default for purposes such as research, innovation, policymaking, and training.

Key milestones include:

- By 2026, member states must designate a Health Data Access Body to manage requests. France has already created the Office for Access to Health Data (ORAD) in anticipation.

- By 2029, cross-border access to datasets must be operational, allowing a researcher in Dublin, for example, to request access to French or German datasets through a unified European procedure.

France has played a coordinating role in this process. In July 2022, the European Commission selected a consortium led by the French Health Data Hub to run the HealthData@EU (EHDS2) Pilot for the secondary use infrastructure—a multinational consortium of around 16 partners across 10 countries, including national data platforms and EU agencies. France is also an active participant in TEHDAS2, the joint action involving 29 European countries that is developing governance and technical building blocks for the European Health Data Space. (ehds2pilot.eu, Public Health, Tehdas)

The EHDS is expected to be transformative by enabling cross-border, privacy-preserving reuse of health data through national Health Data Access Bodies and the HealthData@EU network. This will facilitate the creation of very large, multi-country cohorts—particularly valuable for rare diseases, precision medicine and training robust AI models. For France, alignment with the EHDS ensures that national investments feed into a broader European effort, reinforcing both sovereignty and collaboration. (Public Health, European Commission)

6. Governance, Transparency, and Citizen Empowerment

A national health data system cannot function without public trust. France has learned from past controversies, such as the 2016 debate over the SNDS law, that citizens are wary of opaque data reuse. The new strategy therefore emphasizes transparency, participation, and empowerment.

- A Stakeholder Forum has been established, bringing together patients, healthcare professionals, hospitals, researchers, and industry representatives to discuss governance.

- A forthcoming national portal will allow citizens to see how their data is used, and to exercise rights such as opting out of secondary use.

- Public registries list all authorized projects, including their objectives, datasets used, and results obtained. This visibility is crucial for accountability.

- Access procedures are being simplified: delays, which currently average 9–12 months, are targeted to fall below 8 months by 2027, in line with EHDS requirements.

Oversight is provided by the CNIL (Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés), France’s independent data protection authority, which reviews projects and ensures GDPR compliance.

This governance model embodies a key principle: health data belongs to citizens, but it can serve the public good if managed transparently and ethically.

7. Security, Sovereignty, and High-Performance Computing

Security and sovereignty are not negotiable. Health data is among the most sensitive categories of personal information, and its misuse could have profound consequences. France has therefore established strict requirements:

- Hosting is expected to comply with SecNumCloud certification, issued by ANSSI (the French cybersecurity agency). This guarantees both technical security and legal sovereignty.

- Sensitive projects, especially those involving genomic or imaging data, are conducted in secure data bubbles, isolated environments with controlled access.

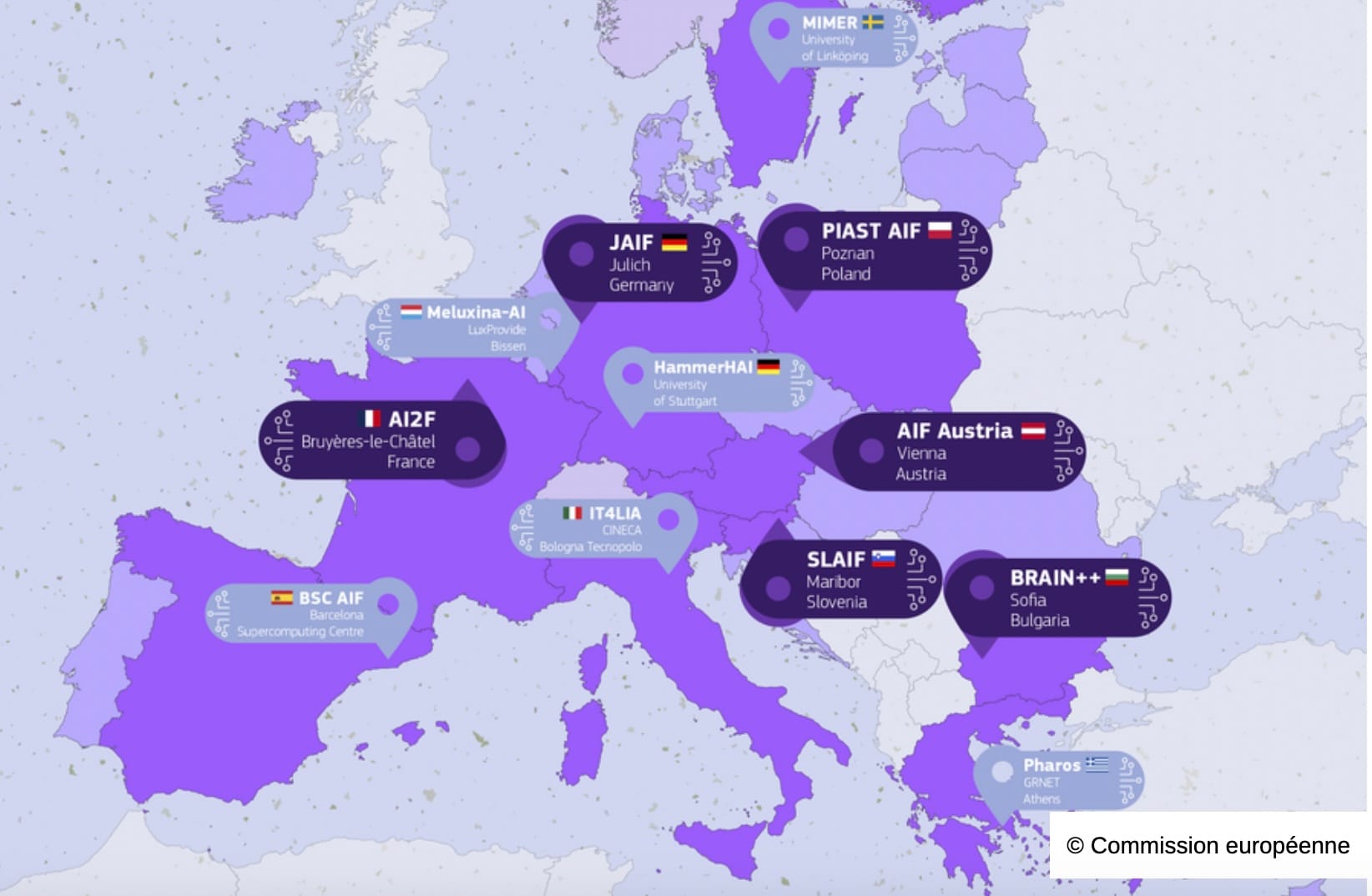

- High-performance computing is provided by GENCI, through its centres in Montpellier (CINES), Orsay (IDRIS), and Bruyères-le-Châtel (TGCC). These infrastructures allow researchers to train large AI models while maintaining data security.

This emphasis on sovereignty distinguishes France’s approach. While some countries rely on global cloud providers, France insists on European jurisdiction and certified infrastructures, ensuring that health data remains protected under European law.

The construction of a national health data infrastructure in France represents a decade-long effort to transform scattered administrative records into a coherent, usable, and sovereign resource. With the SNDS as its backbone, the Health Data Hub as its enabler, and France 2030 as its financial engine, the country has positioned itself as a European leader in health data.

By aligning with the EHDS, strengthening governance, and investing in secure infrastructures, France has created the conditions for data to become the fuel of trustworthy AI in healthcare. The next challenge, explored in the following section, is how to harness this data through artificial intelligence—ensuring that innovations improve care, support professionals, and respect citizens.

Part II – Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare

1. Introduction: Why AI in Healthcare Matters Now

Artificial intelligence (AI) has become one of the most promising technologies of our time. In healthcare, it holds the potential to transform how diseases are detected, how treatments are delivered, and how systems are managed. From algorithms that can analyze radiology images with remarkable accuracy, to predictive models that anticipate hospital readmissions, AI promises efficiency gains, cost savings, and better patient outcomes.

Yet the introduction of AI into healthcare is not straightforward. It raises questions about trust, regulation, evaluation, and professional practice. Unlike consumer technologies, medical applications must meet stringent standards of safety and ethics. Moreover, healthcare systems differ in their infrastructures and governance, shaping how AI can be adopted.

France and Ireland illustrate two different but complementary approaches to AI in healthcare. France has invested heavily in building large-scale infrastructures and national strategies, while Ireland has focused on agile experimentation, pilot projects, and strong academic-industry partnerships. Both face common challenges under European regulation, notably the AI Act and the European Health Data Space (EHDS). Understanding these differences and synergies is key to building cooperation.

2. The French Institutional Landscape

France’s AI strategy in healthcare has emerged in the context of significant national investments in health data. Institutions involved include:

- Ministry of Health and Prevention and the Digital Health Delegation (DNS): responsible for defining national strategy and coordinating implementation.

- Health Data Hub (PDS): providing secure access to national datasets and enabling AI training.

- Haute Autorité de Santé (HAS): evaluating medical devices and AI systems, developing guidelines for clinical and economic assessment.

- CNIL (Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés): ensuring compliance with data protection law and GDPR.

- National research bodies: Inserm, Inria, CEA, and CNRS contribute to algorithm development, ethical frameworks, and pilot projects.

France’s approach has been participatory: in 2025, over 70 stakeholders (hospitals, startups, patient groups, agencies) took part in consultations to define the national AI strategy for healthcare. The process emphasized regulation, evaluation, training, and sustainable funding.

Despite these strengths, the French system is often perceived as complex and slow. Access to data can take months, certification of AI devices is lengthy, and coordination between agencies is sometimes challenging. Policymakers acknowledge these issues and seek to streamline procedures, especially under the EHDS framework.

3. The Irish Institutional Landscape

Ireland, with a smaller population of 5.3 million, has taken a different path. Rather than building a single massive infrastructure, it has pursued incremental digitalization and targeted innovation initiatives. Key institutions include:

- Health Service Executive (HSE) – Digital Transformation and Open Innovation: leading national projects in digital health, including the deployment of the Individual Health Identifier (IHI) and pilots for Electronic Health Records (EHR).

- eHealth Ireland: a programme launched to accelerate the digital transformation of the health service, focusing on interoperability, digital patient services, and infrastructure.

- Insight Centre for Data Analytics: one of Europe’s largest data science research centres, with strong expertise in AI for health applications.

- ADAPT Centre: specializing in digital content and AI-driven personalization, with growing applications in healthcare.

- CeADAR (Centre for Applied Data Analytics and AI): Ireland’s national technology centre for AI, with a mandate to support SMEs and health-related use cases.

- Health Innovation Hub Ireland (HIHI): facilitating collaboration between companies and the health system, testing new technologies including AI in real-world hospital environments.

Ireland’s health data and AI ecosystem is marked by agility and strong collaboration between academia, healthcare providers, and industry. Through the Health Innovation Hub Ireland (HIHI), pilot projects enable new technologies to be tested rapidly in real hospital settings. Leading research centres such as Insight and ADAPT contribute cutting-edge AI expertise, while CeADAR acts as a national bridge to industry, ensuring that innovations can be translated into practical applications.

Challenges remain: Ireland does not yet have a fully deployed EHR system nationwide, and data infrastructures are fragmented. However, its small scale allows for flexibility and rapid experimentation, which larger countries sometimes lack.

4. Comparative Analysis: Two Models, One Goal

Comparing France and Ireland reveals differences in scale, governance, and institutional arrangements, but also complementarities.

4.1 Scale of Data Infrastructures

- France has the SNDS, covering 67 million people, and hospital data warehouses representing 80% of hospital activity. This scale is ideal for training AI models.

- Ireland is building its Individual Health Identifier system and piloting EHRs. Data is less centralized but can be mobilized through targeted initiatives, especially in specific hospitals or disease areas.

4.2 Governance and Regulation

- France has multiple agencies (HAS, CNIL, Ministry, Health Data Hub), providing strong oversight but sometimes slowing procedures.

- Ireland’s governance is leaner, with HSE Digital leading projects and HIHI enabling agile pilots. Regulatory oversight is provided by the Data Protection Commission (DPC), aligned with GDPR.

4.3 Research and Innovation Ecosystem

- France benefits from large public research bodies (Inserm, Inria, CEA) and significant funding under France 2030.

- Ireland has concentrated excellence in centres like Insight, ADAPT, and CeADAR, with strong links to SMEs and international industry (pharmaceuticals, medtech, big tech multinationals present in Dublin, Cork, Galway).

4.4 Professional Training and Adoption

- France is integrating AI and digital health into medical curricula, but implementation is gradual.

- Ireland emphasizes continuing professional development and short innovation cycles, often involving clinicians directly in pilot projects.

In short, France offers scale and national coordination, while Ireland provides flexibility and innovation agility. Both face the same challenge: ensuring that AI is not only developed but actually used in daily healthcare practice.

5. Shared European Frameworks: The AI Act and EHDS

Both countries operate within the same European regulatory environment.

- AI Act (Regulation 2024/1689): Classifies most AI in healthcare as “high-risk.” France, with its structured evaluation bodies (HAS, CNIL), is well-prepared but must streamline processes. Ireland, with fewer agencies, may adapt more quickly but must build capacity for rigorous assessments.

- European Health Data Space (EHDS): By 2029, both France and Ireland must enable cross-border access to health datasets. France already has the SNDS and ORAD; Ireland is building its EHR pilots and data infrastructures. For Ireland, participation in EHDS may be a catalyst to accelerate digitalization.

The EHDS and AI Act create a level playing field: regardless of size, all member states must meet the same requirements. This opens the door for cooperation, with France sharing its experience in data governance and Ireland offering insights into agile implementation.

6. Bridging Two Approaches: Complementarities in Practice

The differences between France and Ireland should not be seen as obstacles but as opportunities for complementarity.

- Data scale vs. innovation testbeds: France’s massive datasets can fuel AI models, while Ireland’s hospital pilots can provide real-world validation. A French-developed algorithm could be tested in an Irish hospital setting more quickly.

- Governance expertise vs. agility: France can share lessons on evaluation and ethics, while Ireland can showcase methods for rapid adoption.

- Research collaboration: Insight Centre and Inria, CeADAR and Health Data Hub, HIHI and French university hospitals all represent potential bilateral bridges.

- European role: Both countries, though different in size, contribute to the same European frameworks. France ensures critical mass, Ireland demonstrates adaptability. Together, they strengthen Europe’s position against global competitors.

Artificial intelligence in healthcare is not only about technology. It is about institutions, governance, professional practices, and citizen trust. France and Ireland illustrate two valid models: one based on large-scale infrastructures and structured governance, the other on agility and pilot projects.

Neither model is superior; both are necessary. Large datasets are useless without practical validation, and small pilots need scale to become sustainable. The future of AI in healthcare in Europe will depend on combining these strengths.

For France and Ireland, the opportunity is clear: collaborate under the European frameworks, learn from each other’s approaches, and build a common path where AI serves not just efficiency, but patient care and public trust.

Part III – Applications and Case Studies

1. Oncology: Early Detection and Diagnosis

Cancer remains one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide. In France, around 430,000 new cases are diagnosed each year, and nearly 150,000 deaths are recorded annually. Early detection is crucial: when breast cancer is diagnosed at stage I, five-year survival exceeds 90%, whereas at stage IV it falls below 25%.

Artificial intelligence is increasingly used to support early detection. In France, several university hospitals have piloted AI-assisted radiology workflows in mammography, where the algorithm acts as a “second reader” alongside radiologists. International studies have shown that such systems can reduce missed cancers and improve consistency, though results vary depending on datasets and clinical settings.

In pathology, high-resolution digital scanners are being deployed to convert histological slides into digital images. AI tools are then tested to help identify malignant cells and prioritise cases. Early evaluations suggest that these solutions may accelerate diagnosis and alleviate the workload of pathology departments, but large-scale validation is still ongoing.

International perspective:

- In the United States, large private providers such as Mayo Clinic and Memorial Sloan Kettering have partnered with tech companies to develop similar tools, though data access is often fragmented across insurers and hospitals.

- In China, AI-based screening programs for lung and liver cancer are deployed at population scale, with strong government backing but less emphasis on transparency.

- In the UK, the NHS has launched AI pilots in breast cancer screening, but progress has been slower due to governance hurdles.

France–Ireland synergy: France’s datasets enable robust training, while Irish hospitals, through HIHI pilots in places like St James’s Hospital Dublin or Cork University Hospital, could serve as agile testbeds to validate tools in real-world settings.

2. Chronic Diseases: Personalized Prevention and Risk Prediction

Chronic diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) account for the majority of healthcare spending. In France, they represent around 60% of hospital admissions and nearly 70% of healthcare expenditures.

Artificial intelligence is increasingly explored to support prevention and management. Using the SNDS and hospital data, research teams have developed predictive models to estimate the risk of cardiovascular events or to identify diabetic patients at higher risk of complications such as foot ulcers or kidney disease. These models aim to help physicians target high-risk individuals for closer monitoring and preventive interventions.

While early pilot projects suggest that targeted prevention with AI tools could reduce hospitalisations and optimise resource use, large-scale evidence and economic evaluations are still in progress.

International perspective:

• In the US, companies such as IBM Watson Health attempted large-scale chronic disease management initiatives, but many struggled due to fragmented data systems and questions over clinical and cost-effectiveness.

• In China, major technology and health platforms are deploying AI-driven population health systems that integrate lifestyle, wearable, and medical data—although with more limited transparency and citizen oversight compared to EU approaches.

• In the UK, the NHS AI Lab within NHS England has piloted risk prediction models in diabetes and other chronic diseases, but integration with general practice (GP) systems continues to pose challenges.

France–Ireland synergy: Ireland, with its smaller population and developing EHR pilots, offers an ideal environment to test AI for personalized prevention at community level. Projects could focus on rural populations or chronic disease management in primary care, where Irish GPs have close patient relationships.

3. Hospital Logistics and Operational Efficiency

Beyond direct patient care, AI is also being tested in the “hidden” dimensions of healthcare: logistics, resource allocation, and administration. In French hospitals, predictive models are being developed to optimise drug stock management, with the aim of reducing shortages and minimising waste of perishable medicines. Pilot projects in operating room scheduling have reported gains in efficiency, enabling more procedures to be carried out with the same resources. In emergency departments, AI tools are being trialled to predict patient flows and support triage decisions, with early results suggesting shorter waiting times.

International perspective:

- US hospitals like Johns Hopkins have deployed AI to manage operating rooms and bed capacity, reporting annual savings of tens of millions of dollars.

- China’s “smart hospitals” integrate AI-driven logistics at scale, though often prioritizing efficiency over patient autonomy.

- The UK NHS has used AI for scheduling pilots, but limited interoperability across trusts has slowed adoption.

France–Ireland synergy: While France has large-scale data to optimize national logistics, Irish hospitals could test lightweight AI tools in smaller facilities, offering lessons in scalability and usability for mid-sized hospitals across Europe.

4. Clinical Documentation and Professional Support

Clinician burnout is a growing crisis. French doctors spend 30–40% of their time on administrative tasks, according to surveys. AI transcription and natural language processing tools have proven effective in reducing this burden.

In pilot projects, French physicians using AI assistants saved 30 minutes per day, equivalent to regaining two to three consultations daily. Automatic structuring of medical notes improved coding accuracy, ensuring correct reimbursement and better quality of data for secondary use.

International perspective:

- In the US, companies like Nuance (now Microsoft) dominate the medical transcription AI market, widely deployed in hospitals.

- China has invested heavily in speech recognition for Mandarin, integrating AI assistants into electronic records.

- In the UK, pilots are ongoing but adoption remains patchy.

France–Ireland synergy: Ireland’s relatively smaller GP and hospital networks make it a perfect ground to test user-friendly transcription tools, focusing on clinician acceptance and workflow integration.

5. Research and Clinical Trials

AI has the potential to revolutionize biomedical research. In drug discovery, machine learning models can already screen millions of molecular compounds to accelerate the identification of promising candidates. In clinical trials, researchers are experimenting with synthetic control arms, which in oncology and rare diseases have been reported to reduce required sample sizes by 15–30%. Such approaches could lower costs and limit patient exposure to ineffective treatments, though broad regulatory validation is still needed. In parallel, the Health Data Hub supports the development of federated learning approaches, allowing AI models to be trained across hospitals without centralizing sensitive data—thus preserving privacy while leveraging the diversity of clinical datasets.

International perspective:

- In the US, pharmaceutical companies are integrating AI into R&D pipelines, but often rely on proprietary datasets.

- China is promoting state-led platforms combining genomics, imaging, and AI at national scale.

- The UK’s NHS has established partnerships with industry (e.g., AstraZeneca, DeepMind) but faces debates on data governance.

France–Ireland synergy: Ireland’s strong pharmaceutical and medtech industry (Pfizer, Novartis, Medtronic) combined with French research infrastructures creates fertile ground for joint AI-enabled clinical research, especially under Horizon Europe programmes.

6. System Governance and Policy Planning

At the macro level, AI can help governments and insurers manage entire health systems. France is experimenting with digital twins of the healthcare system: virtual models simulating patient flows, resource allocation, and policy scenarios. During the COVID-19 pandemic, such models were used to anticipate ICU demand.

AI dashboards consolidate national indicators, allowing policymakers to detect trends such as vaccine hesitancy, regional inequalities, or emerging epidemics.

International perspective:

- The US CDC uses AI to monitor epidemics, though with uneven coverage.

- China integrates AI surveillance into national health policy, but often with limited transparency.

- The UK has piloted regional dashboards, but fragmentation across NHS trusts remains a challenge.

France–Ireland synergy: Ireland’s smaller system offers a controlled environment to develop and validate AI governance tools, which can later be scaled to France. Collaboration could focus on areas such as health inequalities, rural access, and workforce planning.

France’s approach to AI in healthcare brings together several complementary strengths. The scale and depth of the SNDS and hospital data warehouses provide a solid basis for training and validating AI models. A strong regulatory and ethical framework ensures that these solutions are aligned with European requirements for privacy, safety, and trust. At the same time, this framework helps create conditions where innovations are not only responsible but also commercially relevant and ready for deployment across European health systems. Finally, France benefits from a rich innovation ecosystem, with leading research centres, university hospitals, and a growing number of startups supported by France 2030.

This combination positions France as a constructive partner in building a European model of healthcare AI that is both trustworthy and practical, offering opportunities for collaboration and scaling with agile ecosystems such as Ireland’s.

Conclusion and Outlook

1. France’s Progress 2025–2028: Building Blocks Rather Than Final Achievements

Between 2025 and 2028, France has made measurable progress in structuring its health data and AI ecosystem. Much of this progress should be seen not as definitive achievements, but as important building blocks towards a longer-term transformation.

The National Health Data System (SNDS) has expanded in scale and diversity, offering researchers broader opportunities to conduct longitudinal studies. The Health Data Hub has gradually become a reference point for secure access, with several hundred projects authorized and lessons learned about governance and transparency.

Investments under France 2030 have helped hospitals and research cohorts to begin aligning their infrastructures, although interoperability and quality remain uneven. In parallel, France has contributed actively to the European Health Data Space (EHDS) process, preparing to become one of its national nodes.

In the field of AI, the strategy co-developed with hospitals, patients, startups, and agencies has clarified the key priorities: regulation, evaluation, training, and sustainable funding. Several pilot applications—such as AI-assisted mammography, predictive models for chronic disease, and transcription tools for clinicians—have shown promising results.

These are not end points. They represent the first steps of a longer journey, where adoption remains uneven, governance is still evolving, and the cultural integration of data and AI into daily healthcare practice is just beginning.

2. Strategic Perspectives Towards 2030

Looking ahead, France aims to consolidate these foundations rather than reinvent them. The horizon of 2030 offers both opportunities and challenges.

- Data infrastructures will need to be enriched with imaging, genomics, and primary care data. Ensuring quality and interoperability will be just as important as scale.

- AI adoption in practice will depend on sustained efforts in professional training, workflow integration, and trust. It is not certain that all pilots will scale successfully, but the ambition is to make AI a routine part of clinical and preventive care.

- Citizen trust remains a delicate balance. Mechanisms such as a national portal for exercising rights or public registries of projects are steps forward, but their effectiveness will depend on ongoing dialogue and responsiveness to concerns.

- Financing and sustainability will require careful attention, so that digital health is not dependent solely on special programmes like France 2030, but becomes part of the ordinary health system budget.

These perspectives underline that progress will be incremental. By 2030, France will likely have advanced significantly, but the process will remain one of adaptation and learning.

3. Remaining Challenges

Several challenges continue to shape the outlook:

- Delays and complexity in accessing data, which France is working to reduce but has not yet fully resolved.

- Variation in adoption across hospitals and regions, with some institutions well advanced and others still at the starting line.

- Professional engagement, where enthusiasm coexists with skepticism about liability and workload.

- Global competition, which reminds Europe of the importance of building its own path without assuming it can replicate the scale or speed of the US or China.

Recognizing these challenges is important. They show that France’s path is neither linear nor guaranteed, but rather an ongoing process requiring persistence and adjustment.

4. France in an International and European Context

Compared internationally, France’s model is distinctive for its emphasis on sovereignty and ethics, while also facing adoption challenges similar to those of other countries.

· The United States is recognised for its rapid innovation, though its health data landscape remains fragmented across payers and providers.

· China demonstrates remarkable capacity for large-scale deployment, with a strong focus on integration of health and digital infrastructures, though with governance approaches that differ from Europe’s emphasis on individual rights.

· The United Kingdom has advanced through public–private partnerships, yet continues to address challenges around interoperability and public trust.

· Germany moves forward cautiously, placing strong priority on patient control and consent mechanisms, sometimes at the expense of speed of implementation.

5. Outlook Scenarios

Several possible scenarios emerge for 2030:

- Steady Progress: AI becomes a familiar but not universal tool; data infrastructures expand, though with gaps; citizen trust remains fragile but manageable.

- Accelerated Adoption: Pilot projects scale successfully; interoperability improves; chronic disease management and oncology show measurable population-level benefits.

- Stalled Momentum: Trust issues, funding constraints, or limited professional uptake slow progress, leaving many initiatives confined to pilots.

France’s actual trajectory will likely combine elements of all three. The most realistic expectation is gradual progress, punctuated by breakthroughs in some areas and slower movement in others.

6. Opening Towards Ireland and Other Partners

In this evolving landscape, international cooperation is not optional but necessary. Ireland, in particular, offers complementary strengths: smaller scale, agile pilots, strong academic centres, and a collaborative innovation ecosystem.

While France develops large-scale infrastructures, Ireland can provide real-world testbeds to validate tools in flexible hospital environments. Shared training programmes and joint research projects could strengthen capacity in both countries. Above all, participation in EHDS and Horizon Europe offers a natural framework for collaboration.

For France, such partnerships are an opportunity to test and refine its tools beyond its borders. For Ireland, they offer access to large-scale datasets not yet available nationally. Together, they can make a modest but meaningful contribution to the broader European ambition.

France’s national strategy on data and AI in healthcare represents an evolving but steadily advancing journey. It has already produced significant infrastructures, frameworks, and pilot applications that are beginning to show real impact. The key task now is to extend adoption, strengthen trust, and ensure long-term sustainability. The path forward is less about bold declarations than about consistent progress, shared learning, and collective responsibility. By contributing its scale and growing experience to the European project—while continuing to learn from partners who bring agility and innovation—France can help shape a balanced and forward-looking ecosystem. If these elements are combined, Europe as a whole, with France and Ireland among its contributors, will be well placed to build a healthcare system where data and AI become trusted, practical tools serving patients, professionals, and society.